Few scientists, however lustrous their reputations as “speakers,” are well prepared to do an effective teen Café; they often need some preparation. So, once you have identified a presenter using the “10 Tips for Finding Great Teen Café Presenters”, what’s next?

Few scientists, however lustrous their reputations as “speakers,” are well prepared to do an effective teen Café; they often need some preparation. So, once you have identified a presenter using the “10 Tips for Finding Great Teen Café Presenters”, what’s next?

It is well established that the “information deficit” approach to science communication too often used in the context of professional society meetings, lecture series, or the classroom—is ineffective. This one-way transmission of facts from an expert to an information-deficient lay audience is especially ineffective for teens.

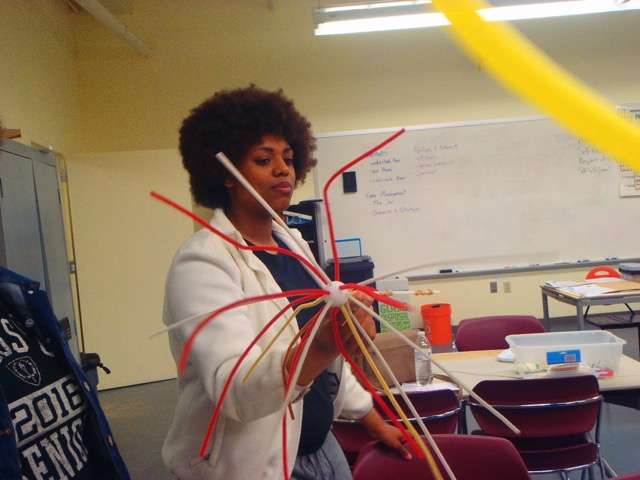

An effective Café presentation requires full engagement between the Café presenter and the teens, who need to be met where they are. The presenter needs to be able to calibrate his or her presentation—often on the fly—to existing knowledge. It is important to make a connection wherever possible to their daily lives. Hands-on activities that actively engage the teens help to cement the science message. Ideally, these interactions take account of current knowledge, misconceptions, biases, and cultural and other affective responses.

The degree of engagement needed to spark teen interest in science topics is unfamiliar and daunting to many Café scientist-presenters, even those with much experience in public speaking; most have been trained to approach science communication in the information deficit mode. But our experience has been that with coaching, after some initial trepidation the scientists rise to the occasion.

Starting from identification of a scientist as likely to be a good candidate for our teen Café, here are the steps we typically follow in preparing them in the Cafe Scientifique New Mexico.

Initial contact. We send them an email summarizing our program and indicating that they have been recommended as someone who could do a good Café presentation. The email also emphasizes the importance of interactivity, meeting the teens where they are, and our desire to have an accompanying “hands-on” activity. Often there will be a follow-up phone call to answer initial questions.

Rarely will a scientist simply say they are not interested—most are likely to say, “sounds like fun”—provided they are contacted months in advance. If they are contacted even a month or two in advance, they are likely to either have their calendars already full or feel they will not have adequate time to prepare; then they will turn us down.

Guidance document. Assuming things are go, we next send them our document, “Guidance for Café Presenters.” The Guidance document stresses the importance of knowing the audience. Teens will readily engage with a presenter on some hot science topic if it is accessible to them. The presentation needs to be free of jargon and delivered in an engaging manner at an entry level so that teens will be pulled in and be able to develop new mental images.

It is important that presenters not try to cover the whole breadth of a science topic, thus creating too many new mental pictures for the teens to try to process at once. A better approach is to organize the presentation around one essential provocative idea or concept, and let everything flow to it. This we refer to as the Most Important Thing, an idea deliberately designed to be accessible to the teens. It is most effective if a presenter gets across the Most Important Thing by telling a story.

Meet for coffee. We arrange to meet with the presenter informally and just talk over what he or she will present. This is an opportunity to help the presenter identify the Most Important Thing—plus no more than three take-away ideas or images—and thus focus his or her thinking. It is an opportunity to emphasize that it is best to assume the audience knows nothing at all about the topic. It is also an opportunity to review best practices in PowerPoint presentations. We start them thinking about a hands-on activity. These meeting are also of great value in establishing a personal connection with the presenter, which will carry through the Café series and beyond.

Critique an initial PowerPoint slide set. In advance of a dry run, we ask the presenter to send a draft of their PowerPoint slide set and we constructively critique it. Typically, the number of slides is reduced dramatically, as is the number of words in the slides. Jargon is ruthlessly weeded out. There needs to be a judiciously selection of very simple, colorful slides that are specifically designed to help create mental images of the most essential concepts in the mind’s eye of the teen.

The essential dry run. We have come to believe that the dry run is an essential part of scientists preparation. We also discovered that dry runs are most effective if they are held with a small group of Youth Leaders; they are the ones that can give the most relevant feedback. The dry run has proven exceedingly valuable in getting the presentations pitched at the right level and the graphics comprehensible. It also serves to overcome a certain intimidation factor for many presenters concerning the prospect of presenting before an unfamiliar audience. While many of our presenters have initially told us they are experienced at presenting to the public and never do a rehearsal, every presenter has told us afterward that the experience was well worth their time. This presenter comment is typical:

“The dry run was immensely valuable. It helped me select appropriate verbiage and content for the presentation. It also helped me gauge the level of delivery. Furthermore, I found the student input extremely important in identifying what their peers would find interesting. After the dry run, I made significant changes to the presentation, including the elimination of confusing content, identification of real-world connections, and simpler examples.

Critique each presentation. Typically, a presenter will present at three or four of the five sites in our node. We try to get with the presenter and provide constructive feedback after each presentation. This highlights one virtue of having multiple sites: the presenter is able to hone and perfect his or her presentation progressively through the Café series. We plan to experiment with introducing a more formal rubric for critiquing the presentations.

[i] Nisbet, M. C. and Mooney, C. (2007a). Framing Science, Science 316, 56.; Nisbet, M.C. and Mooney, C. (2007b). The risks and advantages of framing science – Response. Science 317, 1169-1170.

[ii] Drawn in part from Mayhew, M., and Hall, M., Science Communication in a Café Scientifique for High School Teens. Science Communication, 34 (4), 547-555, DOI 10.1177/ 1075547012444790