The secret of success of the Teen Science Café model is that it is designed to be both for and by the teens. This is one of the Core Design Principles of the Teen Science Café Network:

The secret of success of the Teen Science Café model is that it is designed to be both for and by the teens. This is one of the Core Design Principles of the Teen Science Café Network:

Teens gain a sense of ownership of their program through opportunities for leadership. Teen Leadership Teams take responsibility for most all aspects of café events, including actively promoting the program with their peers in their schools and communities, planning and leading the programs, helping to prepare the presenter, and documenting the event in video, photos, and blog posts, with adult leaders providing support in the background.

Teens’ perception that they own and are responsible for all aspects of their program is fundamentally different from their perception of a program directed by an adult with some intended benefit for teens. Although many teens eagerly volunteer to be teen leaders, their success in this role is heavily dependent on the leadership skill of the adult leader who works with them. This adult leader skill is another of the Core Design Principles:

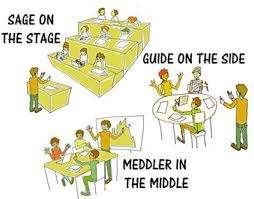

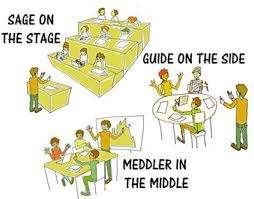

Each café site has one or more adult leaders who are committed to the program. The adult leaders must have the energy and dedication to organize and support the work of teen leaders. The role of the adult leader is first and foremost to instill in the teens a proactive mind set and a sense of freedom to take charge and responsibility for doing what needs to be done to make their program a success, in short to grow as leaders. With this mind set teen leaders will seek to improve and perfect their program. The teens will also have the freedom to make mistakes, but then learn from them and improve.

The adult leader will be there to provide resources and to regularly frame the work that needs to be done, but will allow the teens to take on full responsibility for carrying it out, staying in the background for guidance as needed.

The qualities that an adult leader seeks to instill in teen leaders are much the same as those articulated by the 4-H: confident, responsible, team players, resilient, self-motivated, compassionate, problem solvers, decision makers.

As experience within teen café programs in the Network has demonstrated, an adult leader who is heavy handed in directing the teen leaders will discover that they have a group that is unmotivated, will tend to stand around waiting to be told what to do, and will likely carry out their tasks in a careless and sloppy manner. The program will not function well and its reputation will suffer. The teens will have little opportunity for personal growth.

Adult leaders can be “gateways” or “gatekeepers” and the outcomes from these two approaches are stark, based on our program evaluations (1):

“Adult leaders play a pivotal role in the teen leader experience in terms of how they treat teens, how much support they provide, and the kinds of guidance they give. They serve [either] as gateways [or as] gatekeepers of information about the program and the partner institutions…. As gateways, adult leaders provided teen leaders with information and resources needed to run cafés as well as to grow personally. One teen leader reflected, ‘I think it’s a really strong mutual support system, in that we support them [the adult leaders] in whatever they need us to do to get everything together and they support us into like forming it into what we want it to be’…. Teens who experienced the gatekeeper–type of adult leaders expressed frustration about the support they received from the adult leaders, particularly when the teens sought to take initiative beyond the more traditional roles of marketing, organizing, and running the cafés.” (1)

The same message is found in 4-H’s “Teen Leadership: A Leader’s Manual” (2)

“As an adult leader, your role is to help young people develop a sense of autonomy and personal responsibility. Why is autonomy so important? A sense of autonomy enables youth to make decisions for themselves. Autonomous young people are not subject to the whims and fancies of others but are self-directing…. You can help your members develop individual plans of action. Once common goals are identified, group learning activities can be planned. Adult leaders then have opportunities to provide guidance and encouragement. As goals are completed, a leader can assist with evaluation.

“As an adult leader for this project, your role is to help youth develop to their fullest potential. As a leader, you need to “let go,” to stand back and watch teens practice leadership skills without interference…. At times, you must allow teens to strike out on their own and develop their leadership skills and views on leadership. Once they have learned some of the skills, they must be allowed their freedom and not be constantly told what to do. This is the point at which the adult needs to develop a coaching attitude and offer encouragement, praise, and constructive criticism.

“Research … on adult leadership styles has revealed some clear messages about desirable approaches for working with youth. This research has shown that leaders create effective learning environments when they encourage young people to develop a sense of personal responsibility and to help youth assume more roles even when mistakes are made.

“Youth who participate in these kinds of groups demonstrate higher levels of satisfaction than youth in other kinds of groups. In addition, youth in these kinds of empowering environments learn more life skills and develop more practical skills than youth in other environments.

“In contrast, more control-oriented leaders tend to experience more rebellion, more acting out, more non-attending behaviors, and youth are more dissatisfied with their 4-H experience than youth in autonomy-oriented groups. Youth in control-oriented clubs tend to learn fewer life skills and think of 4-H as less fun than other groups. Ironically, the more a control-oriented leader tries to exert control over youth, the more young people rebel and the more chaos is likely to result.”

This guidance is aligned with a large body of research known as positive youth development (3). In that context, programs like Teen Cafés can be seen as opportunities to achieve significant personal growth of teenagers as they transition to adulthood. Many youth leadership programs have built their programs around positive youth development concepts; the Teen Science Café Network seeks to do likewise.

Positive youth development programs view young people in terms of their potential and its fulfillment. The framework identifies the supports all young people need to be successful, in the here and now and on into adulthood. Positive youth development views young people as resources who have much to offer, rather than as problems that need to be treated or fixed. Having youth as partners means that opportunities must be available for them to try out (and perhaps initially fail), reflect upon, and gain new confidence through challenges and ultimate success. It takes time and commitment to support young people as active participants, rather than mere recipients, and encourage them to have a genuine voice in programs. This emphasizes the crucial role of the adult leader as mentor, rather than “director.”

Positive youth development encompasses psychological, behavioral, and social characteristics that reflect what developmental scientists call the “5 Cs” (3). They are:

Competence: Positive view of one’s ability to successfully carry out actions or make decisions.

Confidence: An internal sense of overall positive self-worth and self-efficacy.

Connection: Positive relationships with the people and institutions with which one interacts.

Character: Respect for societal and cultural norms and standards of correct behavior.

Caring/compassion: A sense of sympathy and empathy for others.

Developmental scientists believe that youth thriving in the 5 Cs develop a sixth “C”: Contribution (to self, family, community, and civil society).

Adult leaders need not be an expert in positive youth development to understand that working with teen leaders as true mentors is a real opportunity to impact their trajectory into adulthood. We know that teenagers need positive, enduring relationships with adults. If a person is to become an adult that functions well in society, a leader, and a perhaps role-model themselves, it makes sense that they need to have relationships with adults who exhibit those traits. If the adult leaders can work effectively with their teens, then those teens might one day learn to work effectively with others.

Nurturing the leadership development of teen leaders is the most important and challenging of an adult leader’s job, but she or he also has other responsibilities, among them coordinating with presenters, keeping the schedule, dealing with parents, and maintaining continuity of the venue. The adult leader is the linchpin of the café program.

To develop as leaders of a teen café program, teens need to learn skills that most will not likely have at the beginning. Thus it is important that monthly meetings of the adult leader with the teen leaders be devoted, not only to preparing for the next café, but to skill development. This means that the teen leaders take turns practicing their roles.

Among the most important role is introducing the presenter as part of a formal opening ceremony and then thanking the presenter as part of a formal closing ceremony. Some teens may come with some experience in public speaking, but most will not. They will need to become conversant with the basics of public speaking and the elements of a formal café opening and closing, and then have the opportunity to practice, with feedback from their peers and the adult leader.

Teen leaders also have important roles on the floor before and during an event. One is to circulate among arriving attendees to chat them up, make them feel welcome and comfortable, and make sure they have any available handouts; this helps the leaders hone their ability to develop social connections with peers. Another is to take the initiative in chatting up the presenter as well; this can help to put the presenter at ease, while increasing the leaders’ confidence in interacting with scientists. A possible outcome is a teen-scientist social connection that may lead to a pathway to a science career. Teen leaders also need to come to an event with questions that can seed discussion and encourage others to ask questions as well. Facility with all these things also takes practice.

Those teens staffing a welcome table also need practice in offering a warm welcome to attendees, distributing comment cards, and facility in making sure attendees sign in with contact information. This process needs to be handled efficiently, especially when faced with a big crowd of attendees. Teen leaders in charge of a food table need practice in coming up with creative menus within budget, laying out the food in a logical manner for efficient serving, and rapid clean-up following the event.

An important part of the training of teen leaders is collaboratively setting expectations with them. Once trained and having clear expectations for all elements of the program, teen leaders are then well positioned to plan upcoming events and make the critical decisions to ensure a success. Allowing them to figure things out for themselves and occasionally make mistakes can be difficult for an adult leader. But swooping in to fix a problem before the teens realize there is a problem only cheats them of the learning experience.

It is also important that the adult leader helps teen leaders reflect on their work after each meeting and café event. This is when they can learn as a group and support one another in both their accomplishments and in the ways they want to improve. Comparing performance to expectations is a critical step in learning and personal growth.

Providing for training of teen leaders and helping them do the planning for an upcoming event within the limited time available for team meetings—while at the same time turning over responsibility for stepping up to their responsibilities to the teens themselves—is a tall order for the adult leader, and this process itself will take practice. And it takes time; but the more teens come to take responsibility for the program, the more efficient it will be and the less of a time burden for the adult leader.

Adult leaders may find the table of “Coping Strategies for Dealing with Problematic Behavior Type and Characteristics” (e.g. “Complainer,” Super Agreeable,” “Negativist”)—developed by the 4-H organization—to be of practical value in their interactions with the teens, but also for the teens to learn these skills so that they can better manage their relations with other team members.

Additional Reading

Building Vibrant Youth Groups by Kirk Astroth, the theme of which is much along the lines of this paper, with some additional insights.

References

(1) Goodyear, A. Kaminsky, and T. McMahon, 2014. Teen Leader Focus Group Evaluation Report. TSCN National Evaluation Team.

(2) University of Vermont Extension, Teen Leadership: A Leader’s Manual. Adapted from Montana State University, Teen Leadership Leader’s Manual, July 1996.

(3) The Positive Development of Youth: Comprehensive Findings from the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development is a longitudinal study that began in 2002 and was repeated annually for eight years, surveying more than 7,000 adolescents from diverse backgrounds across 42 U.S. states. http://www.4-h.org/about/youth-development-research/positive-youth-development-study/

4) Louis Jeantete, Motivating and delegating responsibility to Teen Leaders

http://tappn58.sg-host.com/featured/motivating-and-d…-to-teen-leaders/

5) Natanya Civjan, Influence Without Authority

http://tappn58.sg-host.com/featured/influence-without-authority/

[subscribe2]